[ad_1]

On the 2019 presidential election, Indonesia’s Islamist teams have been on the peak of their affect. They banded along with Joko Widodo’s then rival, Prabowo Subianto, to orchestrate one of the polarising presidential campaigns in Indonesia’s historical past. Although they’ve been battered by authorities repression since Widodo’s reelection in 2019, Islamist teams at the moment are regrouping behind Anies Baswedan and Muhaimin Iskandar within the 2024 presidential race.

In the middle of my doctoral analysis into Indonesia’s Islamist opposition actions within the Jokowi years, I’ve been following Islamist activists, each just about and on the bottom, as they marketing campaign on behalf of Anies and Muhamin’s candidacy. I’ve been struck by how rather more timid these Islamist teams’ marketing campaign rhetoric is in contrast with 2019. Gone are the times when their volunteers would go round from home to deal with to unfold internet-sourced propaganda accusing their political rival of being a Chinese language communist agent who was bent on abolishing Islam from public life and was conspiring to assassinate Muslim leaders—issues they stated about Jokowi in 2019. They now not describe the election in apocalyptic phrases, the place one candidate is portrayed as an evil power whereas the opposite is hailed because the saviour that would salvage Indonesia from impending doom.

As an alternative, Islamist activists in Anies’ workforce and from affiliated volunteer teams have chosen to stress his dedication to what they name “moral politics” (an Islamist euphemism for governance based mostly in Islamic morality), his concrete achievements as governor of Jakarta between 2017 and 2022, and his promise to revive the freedoms and justice which have been eroded below Jokowi. Islamists’ marketing campaign fashion, in different phrases, has shifted from being one characterised by passionate ideological agitation to a extra level-headed programmatic fashion, reflecting the general decline in ideological polarisation throughout Jokowi’s second time period.

However does that imply that Islamists have deserted their ideological beliefs and objectives, or does it merely mirror political expediency? I argue that Indonesian Islamists’ rhetorical moderation is primarily an adaptation to the three key political realities of the late Jokowi years.

Firstly, state repression has made Islamists cautious about embracing overtly sectarian campaigning. Secondly, with Islamists having aligned behind the candidacy of the Anies and Muhaimin, and retaining their choices open with a reconciliation with Prabowo Subianto in a possible second spherical of the presidential election, they’ve sought to not alienate pluralist Muslim voters linked to traditionalist teams like Nahdlatul Ulama (NU).

Third, not like within the aftermath of the mass mobilisations towards the alleged blasphemy of former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, there isn’t a religiously-charged situation round which a dynamic of polarisation can come up. The problems of Rohingya and Israel–Palestine battle have featured within the 2024 marketing campaign, however these points don’t divide Indonesians neatly alongside Islamic–nationalist traces, and supply solely restricted potential for the reactivation of ideological passions within the quick time period.

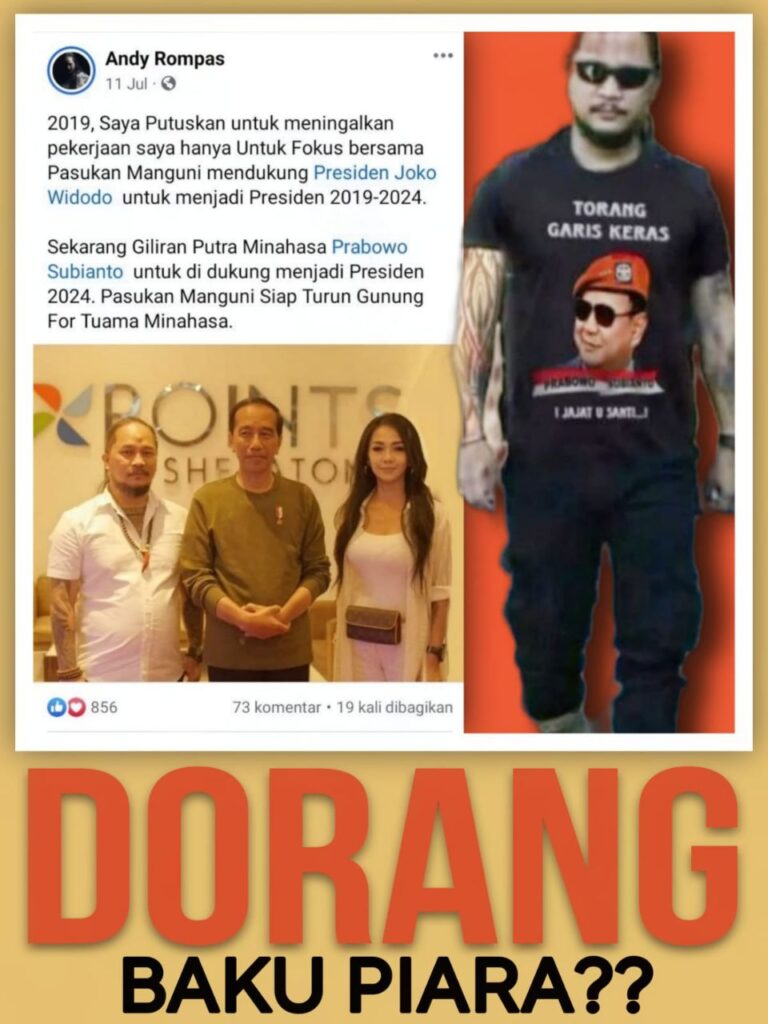

Promotional supplies for a marketing campaign occasion for Anies Baswedan that includes distinguished Islamist cleric and “co-captain” of Anies’ marketing campaign workforce, Yusuf Martak (left)

De-risking spiritual rhetoric

I restrict my evaluation to non-violent Islamist teams akin to FPI—relaunched, after the ban of the Entrance Pembela Islam/Islamic Defenders’ entrance in 2020, because the Entrance Persaudaraan Islam/Islamic Brotherhood Entrance—and the self-styled “Alumni” of the 212 motion activists that led the protests towards former Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama in 2016–17. These teams share comparatively reasonable objectives and strategies in comparison with jihadist extremists. They pursue an Islamisation of society and the state not by way of revolution however by way of gradualist techniques like proselytisation, training, social providers, advocacy, and political participation. They may enthusiastically drum up illiberal sectarian sentiments (which they genuinely maintain) when it advantages them, however stay able to tone it down when their survival is at stake. For this group of non-jihadist Islamists, the objective is to win energy first, then work on the religio-political reform later.

In 2024 as in 2019, direct engagement in electoral politics is an element and parcel of this technique. On 27 September 2023, Anies and Muhaimin visited the FPI chief Rizieq Shihab, as if to safe his blessing, simply earlier than they formally registered their candidacy. As soon as Anies’ candidacy was confirmed, he recruited Yusuf Martak, a detailed confidant of Rizieq, as one of many co-chairs of his success workforce.

Islamists have made it clear that they aren’t giving a clean cheque to Anies. In trade for his or her help, they required Anies and Muhaimin to signal a 13-point “Integrity Pact” which, amongst different issues, affirmed the candidates’ dedication to again the Islamist agenda of combatting secularism, communism, and spiritual blasphemy (for them, a code phrase for the perceived progress within the energy and “conceitedness” of Indonesia’s Christian minority). The settlement additionally stipulated that Anies and Muhaimin would implement public morality based mostly on Islamic norms and enhance peculiar individuals’s financial circumstances by stopping a purported influx of mainland Chinese language staff.

Following the identical formulation as in 2019, in November 2023 FPI and its associates organised a Convention of Non secular Students (Ijtima Ulama) with a view to give their selection of candidate the stamp of non secular authority. The 2023 Ijtima resulted in a spiritual suggestion by “Grand Imam” Rizieq Shihab to vote for Anies and his working mate Muhaimin. The concept is to leverage the grassroots community of FPI and the Brotherhood of 212 Alumni (Persaudaraan Alumni 212, or PA212) to organise marketing campaign actions and the distribution of marketing campaign supplies in help of Anies. As of late 2023, the resurrected FPI boasted branches in 23 out of 38 provinces, whereas formal PA212 buildings have been established in all districts within the 10 most populous provinces; each sped up their growth of native branches with a view to mobilising voters for the 2024 election. That stated, it’s unclear what number of members both organisation truly has—native FPI activists usually double up as PA212 executives.

Though the “Integrity Pact” between FPI and the Anies marketing campaign and the Ijtima Ulama’s endorsement of Anies exhibit a number of the sectarian and xenophobic tone that characterised Islamist activism within the 2019 election, my on-the-ground statement of FPI-linked marketing campaign occasions suggests they’ve cooled down their divisive spiritual narratives for 2024.

A typical marketing campaign in Central Java, for example, would entice between 50 to a couple hundred individuals, although the quantity is likely to be increased in FPI strongholds akin to Banten and Larger Jakarta. Many such marketing campaign occasions that I noticed have been easy (held in mosques, Islamic pesantren boarding colleges, or different free venues) and largely funded by volunteers and donations from native candidates in search of to win the sympathy of Islamist constituencies. Attendees at these occasions obtain free T-shirts, posters, mugs and different merchandise, however I’ve not witnessed any trade of financial items (as has been reported in different candidates’ campaigns). This isn’t shocking given Anies has reported the bottom quantity of marketing campaign funds among the many three presidential candidates.

What was extra hanging to me was the relative lack of non secular zeal and apocalyptic narratives that have been ubiquitous in 2019. Talking at a pro-Anies volunteers assembly in Solo on 9 January, the secretary normal of PA212 Uus Solihuddin instructed the volunteers to de-emphasise lofty ideology and focus extra on concrete programmatic insurance policies. Whereas within the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election Islamist leaders relied on intimidation and fear-mongering to coerce Muslims to vote for Anies (akin to threatening to not carry out funeral prayers for not too long ago deceased Muslims who supported “infidel” candidates), Islamists at the moment are fastidiously avoiding any statements that may be construed as smear marketing campaign, misinformation or sectarian incitement. As PA212’s secretary-general instructed the assembled volunteers,

Keep away from black campaigns! Concentrate on selling the imaginative and prescient and mission of Amin (Anies and Muhaimin), make it viral through the use of plain, simply accessible language. Don’t discuss lofty concepts. Simply discuss low-cost groceries (sembako). As a result of let’s face it, most Indonesian individuals are not at that [intellectual] degree but. Have interaction the individuals by saying issues like: would you like higher healthcare? Would you like low-cost electrical energy? Would you like a driver’s license that applies for a lifetime—no must renew it each 5 years? Then you possibly can reinforce the message by telling them that these are the suggestions of our ulama who’ve signed an settlement with Anies.

The warning round “black campaigns” displays Islamists’ concern of persecution and arrest, a essential issue that explains the shift away from sectarian narratives. (Alfian Tanjung, one other Islamist cleric who was current on the assembly in Solo described right here, had been imprisoned from 2017 to 2020 after being convicted of legal defamation for calling Jokowi and PDI–P “lackeys” of the Indonesian Communist Celebration/PKI).

SAFEnet, an NGO that advocates for freedom of on-line expression, reported in 2022 that the arrest of opposition activists below Indonesia’s Digital Data and Transactions Legislation (UU ITE) has elevated by 26%; most have been costs with defaming state officers and establishments. Islamists are arguably essentially the most focused class of all opposition activists. The truth that Rizieq Shihab is on parole till June 2024, following his launch from jail in July 2022, is a residing reminder of the nice dangers they’re dealing with: as one activist put it, “any tiny mistake might ship Habib Rizieq again to jail, that’s why we should be cautious.”

Yusuf Martak equally instructed a gaggle of pro-Anies volunteers in Klaten and Solo that they need to emphasise his concrete achievements in combating social ills in Jakarta, akin to closing down a significant brothel and a restaurant chain that gave free promotional beers to anybody named Muhammad. It was steered that selling his accomplishments in public morality and infrastructure improvement can be more practical and fewer dangerous than invoking overtly Islamist jargon (e.g. “infidels”, “shari’a”) which are carefully related to radicalism.

Sustaining reasonable help

Final however not least, Islamists felt compelled to tone down their spiritual zeal with a view to appease the reasonable, traditionalist Muslim base of Anies’ working mate, Muhaimin Iskandar.

Associated

The prices of repressing Islamists

The banning of FPI or every other “anti-Pancasila” group isn’t a shortcut to ending deep-seated discrimination towards minorities.

Islamists have been initially dissatisfied by the appointment of Muhaimin as Anies’ working mate due to his pluralist (NU) background, his implication in historic corruption circumstances, and his attendance at a 2023 Coldplay live performance in Jakarta that was protested by FPI on the grounds that the band has proven help for LGBT individuals. But as soon as Rizieq Shihab issued the instruction for the FPI rank and file to help Anies, they fell into line.

Many inside Muhaimin’s NU milieu understand Anies as a “Wahhabi”—a reference to the ultrapuritan model of Sunni Islam related to Saudi Arabia, which has develop into a slur amongst Muslim moderates in Indonesia—on account of his modernist background and shut relationship with the Islamist Affluent Justice Celebration (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera/PKS). That is within the context of an inner rift inside NU: the organisation’s chairman Yahya Cholil Staquf and most of its nationwide board have sided with Prabowo, whereas influential NU kyai (traditionalist spiritual leaders), together with NU’s former chair Mentioned Aqil Siradj, have backed Muhaimin and his get together PKB. In East Java, numerous kyai from Yahya’s camp exhorted their followers to not vote for Anies, saying that he secretly conspired with the banned transnational organisation Hizbut Tahrir and FPI to switch the Indonesian republic with a caliphate.

To allay these suspicions, FPI and the 212 activists have included references to “the preservation of the Unitary Republic of Indonesia (NKRI) and Pancasila” of their Integrity Pact with Anies. In reality, FPI and PA212 have adopted a development set not too long ago by authorities businesses and NU establishments of starting their formal gatherings by singing the nationwide anthem.

Anies shaking fingers along with his supporter, former NU chair Mentioned Aqil Siraj at a commemoration of the birthday of NU cleric KH Bisri Syansuri, Muhaimin Iskandar’s nice grandfather, Jombang, 12 January 2024 (Photograph: creator)

Islamists are additionally calibrating their campaigning with a view to the potential for reconciling with Prabowo Subianto, with some main figures in FPI and PA212 already planning to shift allegiance to Prabowo ought to Anies fail to enter the second spherical. As one senior activist from FPI put it:

We at the moment are campaigning for Anies, sure. However we shouldn’t assault the opposite aspect overzealously. I don’t suppose it’s proper to throw a smear marketing campaign at Prabowo. In any case, he and [his party] Gerindra have accomplished quite a bit for us. Anies promised us plenty of issues, however ultimately he gave extra money and positions to NU. Regardless of Prabowo’s betrayal, it was Gerindra politicians who defended us, gave us authorized help when our members received criminalised. Gerindra advocated for the KM50 trigger [the police shootings of 6 FPI members in 2020] in parliament. So we shouldn’t offend Prabowo an excessive amount of, he’s our greatest possibility if there’s a second spherical.

Palestine and Rohingya supply restricted scope for polarisation

Anti-Rohingya incitement has intensified on social media since late 2023. One video that went viral on Tiktok purported to indicate how Rohingya asylum seekers in Aceh threw away meals that had been donated to them by native villagers. One other alleged that Rohingya asylum seekers in Malaysia had demanded land, warning viewers that they may wish to take over native individuals’s land in Aceh too. This on-line incitement culminated in an incident wherein a whole bunch of college college students in Aceh raided a refugee shelter and compelled the Rohingya to go away. Rights activists and social media specialists contended that the web hate speech was too systematic to be natural; the newspaper Koran Tempo quoted a supply who said that some components inside state safety forces employed the scholar mob with a view to sow disaster.

Some Islamist teams imagine {that a} backlash towards Rohingya asylum seekers has been engineered to discredit Islamists, who had lengthy carried out humanitarian fundraising for Rohingya victims of ethnic cleaning in Myanmar. The net content material that has framed Rohingya as lesser Muslims with sinful habits was subsequently like a slap within the face to Islamists.

Whereas it stays mysterious how the anti-Rohingya marketing campaign happened, or who was behind it, the problem has develop into a degree of rivalry between the presidential candidates. Anies has struck a sympathetic word, saying that Indonesians have a humanitarian responsibility to assist Rohingya Muslims who’ve come asking for defense. Prabowo, then again, has asserted that it’s unfair to impose such a burden on Indonesia, and that the United Nations should be accountable. Ganjar Pranowo, in the meantime, has given a imprecise remark that neither accepts nor rejects the asylum seekers.

Some pro-Anies Telegram channels have unfold a counter-narrative that the Acehnese scholar chief who coordinated the assault on Rohingya was a youth member of Prabowo Subianto’s Gerindra get together, and that Prabowo has sanctioned the discrimination towards one of many world’s most persecuted Muslim minorities. The Rohingya situation has not flared up considerably, with the federal government swiftly offering another shelter for these displaced by group protests in Aceh.

The Palestine situation has in the meantime develop into fertile floor not just for Islamists’ electoral campaigning but additionally for his or her long-term growth and recruitment. The difficulty can also be a “secure” one, as a result of the federal government is extra tolerant of Islamist mobilisation on international conflicts—particularly given Indonesia’s official help for Palestinian freedom—than native ones. In December 2023, for the primary time in 5 years the federal government allowed FPI to carry the 212 Reunion Rally at Jakarta’s Monas sq., on the situation that it was centered on Palestine.

Some Islamist sources instructed me that when their pro-Anies occasions have been prohibited by PDI-P district and village heads in rural West Java, for example, they received across the restrictions by conducting a Palestine solidarity roadshow. They stated that even some PDI–P strongholds might settle for them and have been keen to donate cash if the clerics centered on the plight of Palestine and providing spiritual counselling to the villagers. Many lay PDI-P sympathisers volunteered their cellphone numbers to Islamist clerics after being instructed that they might get free on-line counselling and limitless provides of “holy water”, solely to seek out themselves bombarded with Anies marketing campaign supplies by way of WhatsApp. The Palestine situation stays important for Islamist revival past the election, having large enchantment that cuts throughout partisan cleavage, and it offers Islamists with ample alternatives for fundraising and outreach to new audiences.

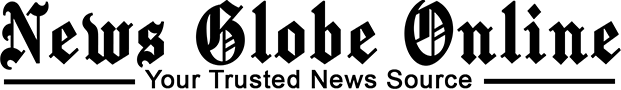

In Indonesia’s outer islands, nevertheless, the Israel–Palestine battle carries extra divisive potential. On 25 November 2023, violent clashes broke out between the Muslim Solidarity Entrance (Barisan Solidaritas Muslim) and a Christian group named Manguni Brigade in Bitung, North Sulawesi. BSM was holding a pro-Palestine rally on the road after they ran right into a convoy of Makatana Minahasa Christians who have been additionally on their option to a cultural parade. Among the Christians carried Israeli flags, which triggering an altercation with BSM that devolved right into a brawl that killed one individual and injured two others.

In video footage that circulated on social media, a number of individuals from Manguni Brigade wearing conventional battle apparel have been seen chasing BSM members; numerous native Muslims joined one other struggle that broke out within the metropolis centre later that night time. The video footage additionally confirmed the Manguni Brigade burning Palestinian flags and destroying an ambulance that belonged to BSM. Islamist on-line channels shortly unfold the movies and talked about jihad towards the “Christian Zionists”. Rizieq Shihab additionally issued a press release demanding that the federal government punish the Zionist supporters who attacked Muslims in Bitung.

Whereas the native battle was swiftly managed by native authorities, its results have lingered and bled into the election. Professional-FPI social media accounts circulated photos of the Manguni Brigade chief sporting a Prabowo T-shirt; in a single image, he was seen posing with Jokowi with the caption within the model shared by Islamists remarking that “that is the rationale Manguni Makasiouw isn’t banned after inflicting riot in Bitung, possible protected by Jokowi”. One other video confirmed an enormous Israeli flag being waved at a PDI–P rally for Ganjar Pranowo. In Central and West Java, some Islamist activists have been making ready to deploy their Laskar (safety or paramilitary organisations) to protect polling stations towards intimidation and fraud they allege is being deliberate by the “pr o-Zionist crimson thugs” (preman merah, a reference to PDI-P’s get together colors).

Islamist on-line propaganda on Laskar Manguni (Supply: Telegram channel monitored by the creator)

Regardless of Islamists’ makes an attempt to make use of the Rohingya and Palestine points to activate the latent sectarian tensions in Indonesian society, the controversy round these points don’t neatly slice the citizens alongside the Islamist vs pluralist traces. Within the case of Israel–Palestine battle, Indonesians no matter their spiritual inclinations are overwhelmingly pro-Palestine. The difficulty isn’t as divisive as within the West. The anti-Rohingya situation has to some extent taken on a political flip, with Anies’ Islamist supporters advocating the rights of Rohingya refugees, whereas Prabowo has solid them as a possible risk to Indonesians’ financial pursuits. As Prabowo stated whereas visiting Aceh on 24 November 2023: “now let’s say we wish to assist the Rohingya. How can we assist, our personal individuals are wanting meals. Round 20% of our kids are malnourished.”

These two points are subsequently unlikely to trigger deepening polarisation. Nevertheless, the Palestine situation significantly offers a fertile floor for Islamists to revive and increase their enchantment (not least as a result of the federal government tolerates Islamist propaganda on international reasonably than home affairs), therefore its usefulness will outlast the election.

Anies–Muhaimin marketing campaign merchandise, that includes the identify of “co-captain” Yusuf Murtak (Photograph: creator)

Conclusion

My statement of the election marketing campaign in city and rural Java reveals a a lot calmer image than the earlier presidential race. In contrast to in 2019, individuals didn’t complain as a lot about an emotionally draining election, marked by id politics, that affected their private relationships with household and pals.

Islamist teams themselves have determined to “calm down” divisive marketing campaign narratives for numerous strategic causes—with out essentially abandoning their long-term ideological agenda. This has partly to do with the significance of not alienating the reasonable traditionalist Muslims, particularly in East Java, that type an necessary a part of the Anies–Muhaimin ticket’s electoral coalition. The stigmatisation of radicalism has additionally contributed to Islamists’ strategic avoidance of ideological messaging. Certainly, Jokowi’s anti-radicalism coverage and counter-polarisation efforts by NU and different pluralist teams have pushed Islamists to the perimeter, no less than in the interim. Furthermore, Islamists have seen that Jokowi’s social help packages have contributed to his excessive approval rankings, fostering a perception that Indonesian individuals care extra about their financial wellbeing than ideology—therefore the Islamists’ pivot to bread and butter points when campaigning for Anies.

Lastly, the reducing depth of ethnoreligious rigidity and partisanship means that post-election riots like these seen in Could 2019 are unlikely. Nevertheless, the violent Christian–Islamist conflict in Bitung reminds us that there’s potential for remoted native conflicts between supporters of various candidates within the lead as much as the election and its aftermath.

[ad_2]

Source link